Why Your VoIP Call Fails Before It Even Rings

Imagine calling a client, hearing one ring, then silence. No voicemail. No error message. Just nothing. This happens more often than you think - and it’s almost always because two devices couldn’t agree on how to speak to each other. Not in language. In codec.

Codec negotiation isn’t a fancy term for IT nerds. It’s the silent handshake that decides whether your voice sounds clear or robotic, whether your call uses 30Kbps or 64Kbps of bandwidth, and whether the call connects at all. If you’ve ever had a VoIP call drop, crackle, or fail outright, the problem likely started here - in the exchange of SDP messages before the first word was spoken.

What Exactly Is a Codec in VoIP?

A codec isn’t software you install. It’s a math algorithm. It takes your voice - analog sound waves - and turns them into digital packets that can zip across the internet. But here’s the catch: not all codecs are built the same.

Take G.711. It’s the old-school standard. Sounds like a landline. Uses 64Kbps. Clean, clear, but thirsty for bandwidth. Then there’s G.729. It cuts that to 8Kbps. Sounds fine for phone calls, but loses some warmth. And then there’s Opus. It’s the new kid. Can deliver CD-quality audio at just 30Kbps. Supports everything from whispered conversations to full-band music. And it adapts on the fly.

Here’s the problem: your iPhone might love Opus. Your office PBX might only know G.711. Your cloud phone system supports both. But unless they talk to each other and pick a mutual language, the call dies before it starts.

The Silent Conversation: SIP and SDP

VoIP calls don’t start with “Hello.” They start with a SIP INVITE - a digital note passed between devices. Inside that note? SDP - the Session Description Protocol. Think of SDP as a menu. Each endpoint lists the codecs it can handle. For example:

- m=audio 40040 RTP/AVP 8 18 0 101

This means: “I’m ready for audio on port 40040. I support payload type 8 (G.711 A-law), 18 (G.729), 0 (G.711 mu-law), and 101 (telephone tones).”

The other side replies with a 200 OK message - its own menu. If there’s overlap? Great. They pick the highest quality codec both support. If not? The call gets rejected with a SIP 488 error: “Not Acceptable Media.” No second chances. No fallback. Just silence.

Three Ways Networks Handle Codec Negotiation

Not all VoIP systems are created equal. How they handle codec negotiation makes a huge difference.

1. Direct Negotiation - No Middleman

Two endpoints - say, a WebRTC browser and a modern SIP phone - talk directly. They compare lists. Pick the best common codec. Simple. Efficient. Often the best quality. But only works if both devices support the same modern codecs. Most enterprise systems don’t.

2. Forced Codec - The Bossy Router

Some systems, like Cisco’s Unified Border Element (CUBE), let admins lock in one codec. Configure it for G.729? Then every call must use G.729. No exceptions. Saves bandwidth. Reduces complexity. But if the other end doesn’t support it? Call fails. Hard stop. No warning. No retry.

3. Transparent Mode - Let Them Figure It Out

This is the “hands-off” approach. CUBE or an SBC just passes the SDP messages between endpoints untouched. No filtering. No forcing. The devices negotiate on their own. Sounds ideal, right? But here’s the catch: if your internal phones support Opus and your external vendor only does G.711, they’ll pick G.711 - and you’re wasting bandwidth on a 64Kbps stream when you could’ve used 30Kbps. One network engineer reported a 15% bandwidth spike after switching to transparent mode.

Why Opus Is Changing Everything

Opus isn’t just another codec. It’s the first that’s truly designed for the modern internet. Unlike G.711, which was built for 1970s phone lines, Opus works on anything - from a 3G connection to a fiber line. It adapts bitrate in real time. It handles speech and music equally well. And it’s open-source, so no vendor owns it.

Since 2019, Opus adoption in WebRTC apps has jumped from 12% to 57% by 2022. Today, 89% of new WebRTC implementations use it. Why? Because users notice the difference. One company saw a 41% drop in dropped calls after switching to Opus. But here’s the kicker: legacy PBX systems don’t speak Opus. So you need transcoding - a middleman that converts Opus to G.711 on the fly. That adds cost. One user reported a $12,000 annual increase in infrastructure bills just to bridge the gap.

The Hidden Problem: Vendor Inconsistency

Here’s what no one tells you: the tech works fine. The problem is implementation.

A 2022 SIP Forum report found that 68% of codec negotiation failures came from inconsistent codec prioritization across vendors. One device might list codecs like this: Opus, G.722, G.711. Another might list: G.711, G.722, Opus. Both support all three. But they pick different ones. Why? Because the first device thinks Opus is best. The second thinks G.711 is safest. Neither talks to the other about preference.

Result? They pick G.722 - the middle ground. Not the best. Not the most efficient. Just… whatever they both agreed on last. It’s like two people trying to pick a restaurant. One wants sushi. One wants tacos. They settle on pizza. Not because it’s their favorite. Because it’s the only thing both menus have.

How to Fix It: Best Practices for Network Engineers

If you manage VoIP systems, here’s what you need to do - right now.

- Map your endpoints. What codecs do your phones, softphones, and cloud services support? Don’t assume. Check the specs.

- Don’t force G.729 unless you have to. It’s outdated. Opus is better. G.722 is better for wideband. Reserve G.729 for legacy systems only.

- Use transparent mode cautiously. It’s great for compatibility. But monitor bandwidth. If you see G.711 everywhere, you’re paying for unused capacity.

- Use an SBC with transcoding. If you have WebRTC users calling legacy PBX, you need a device that can convert Opus to G.711 (or vice versa) on the fly. Don’t try to force everyone to upgrade at once.

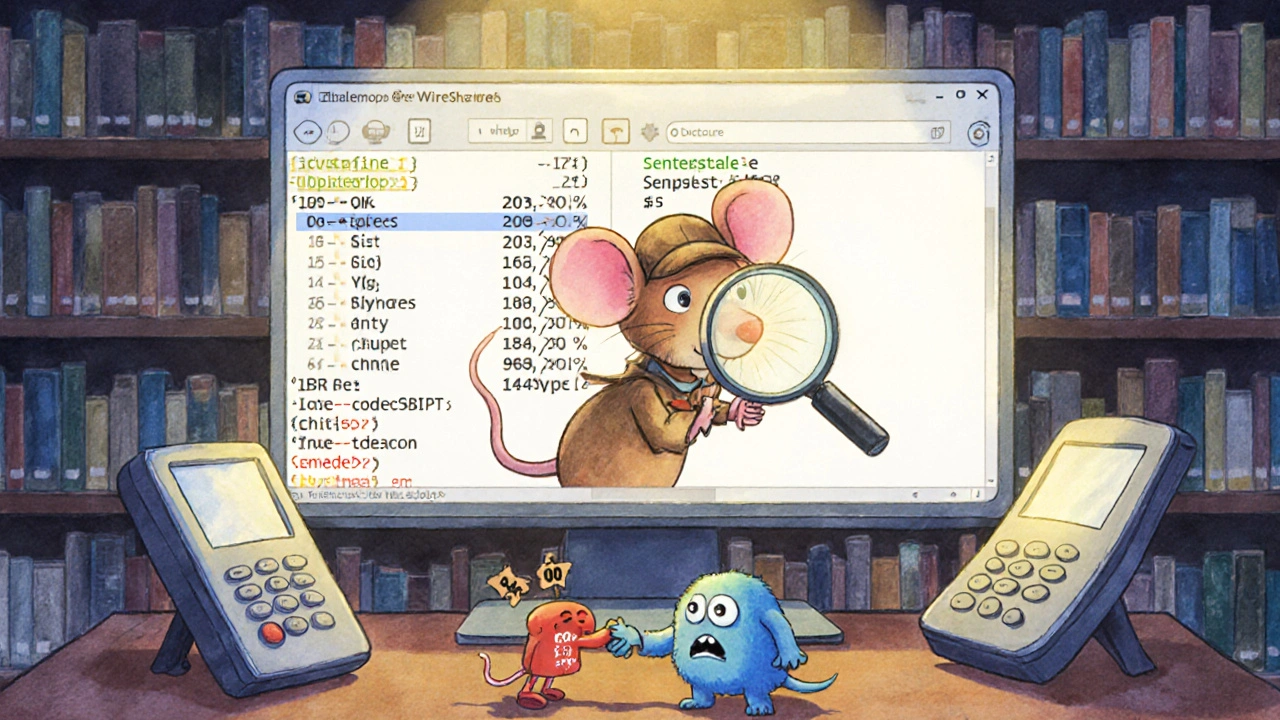

- Check SDP in Wireshark. If calls are failing, grab a packet capture. Look at the INVITE and 200 OK. See what codecs each side offered. Is there any overlap? If not, you’ve found your problem.

What’s Coming Next

By 2025, Gartner predicts 45% of enterprise VoIP systems will use AI to pick codecs based on real-time network conditions. Think of it like GPS for voice: “The network is congested? Switch to 20Kbps Opus. Bandwidth is free? Go full 510Kbps for studio quality.”

Meanwhile, the IETF is working on new standards to make codec negotiation even smarter - especially for WebRTC. And H.323? Dead. SIP and SDP are the only game in town now.

But here’s the truth: the core problem won’t change. Devices will keep being made by different companies. Networks will keep being patched together. And as long as that’s true, codec negotiation will remain the silent gatekeeper of every VoIP call.

Final Thought: It’s Not About Tech - It’s About Alignment

Codec negotiation isn’t about choosing the best codec. It’s about aligning expectations. You can’t have a system where one side assumes Opus is default and the other side assumes G.711 is fallback. Someone has to set the rules.

Whether that’s your SBC, your dial-peer config, or your vendor’s default settings - make it intentional. Test it. Monitor it. Don’t wait for a call to fail before you fix it.

Common Questions About VoIP Codec Negotiation

What happens if two VoIP endpoints don’t share a common codec?

The call fails immediately. The system sends a SIP 488 response - “Not Acceptable Media.” No audio is transmitted. No ringing. No voicemail. The call simply doesn’t connect. This is why checking codec lists in SDP messages is critical during troubleshooting.

Is G.711 still necessary in modern VoIP systems?

Yes - but only as a fallback. G.711 is supported by 99.8% of all VoIP endpoints, including legacy PBXs and basic phones. If you’re connecting to any external system, especially outside your control, G.711 is your safety net. But don’t use it as your primary codec. It’s inefficient. Use Opus or G.722 when you can.

What’s the difference between transparent mode and forced codec on a Cisco CUBE?

In transparent mode, the CUBE passes SDP messages unchanged. Endpoints negotiate directly - you get the best possible codec, but possibly higher bandwidth use. In forced mode, you lock the CUBE to one codec (like G.729). All calls must use that codec. Bandwidth is predictable, but calls fail if the other end doesn’t support it.

Can I use Opus with my old PBX system?

Not directly. Most legacy PBX systems only support G.711 or G.729. To connect Opus-based devices (like WebRTC apps or modern SIP phones), you need an SBC or media gateway that transcodes between Opus and G.711. This adds latency and cost, but it’s the only way to bridge the gap without upgrading your entire system.

How do I test if my codec negotiation is working?

Use Wireshark to capture SIP traffic. Look for INVITE and 200 OK messages. Check the SDP section. Look for the “m=audio” line and the list of payload types. See if there’s overlap between the two sides. Then check if the final codec selected is the one you expected. If you see G.711 when you expected Opus, your system is falling back - and you may be wasting bandwidth.